Published on: August 31, 2022

Authors: Tom Hayes

Topics: People and Culture, Technology, The UK and European Union

Apple’s Tart over Remote Work

Recently the Financial Times, along with many others newspapers, reported that “Apple employees are pushing back against the iPhone maker’s call for workers to return to the office next month, arguing that they have shown they can perform “exceptional work” during two-plus years of flexible arrangements.”

According to the FT: “Apple Together, a group of workers that formed last year when offices around the globe were forced to work remotely because of the pandemic, began circulating a petition internally on Sunday, demanding “location flexible work”.”

Not the first of such battles, and certainly not the last.

It is a good example of social media “employee voice” about which we recently wrote, challenging the entrepreneurial right of management to decide how and where work is organised. In this instance, the “leverage” behind such voice appears to come from the competitive marketplace. Employees look to be saying – “if Apple will not agree to let us do ‘location flexible work’ we will go elsewhere.”

Even if 10,000 employees signed a petition on the matter, that is just 6 - 7% of Apple’s workforce. And the other 90%+.... what do they think? The social media megaphone should not be taken to reflect all employee opinion. Sometimes, it appears to be little more than one of those tricks of the light that turns the shadow of a little mouse into a roaring monster. Turn off the light and it is still a little mouse. Though a little mouse convinced of its own moral righteousness.

How to respond to this challenge is a call only Apple management can make. There is no template, no “right” answer to the question how work should be organised. What works for one company will not work for another.

Who has the right to make that call? Who decides?

How work is organised in the US is, for the most part, unilaterally decided by management in what it believes to be the best interests of the company, other than where workers are unionised, and collective bargaining plays a role. An ever-decreasing role, it must be said, impacting only a small minority of workers.

In the end, the market will decide how work is best organised to maximise organisational value. The “market” is to be understood as being made up of those competitive forces, employee voice, political voice(s), consumer preferences, and technological developments that create the ecosystem within which businesses must work, and in which they succeed or fail.

Markets never work smoothly because, despite what is alleged in economic theory, market players never have access to all relevant information at the time decisions need to be made. Decisions are always made in conditions of uncertainty which is why decisions makers sometimes (often) get things wrong. But over time the good generally pushes out the bad and a new balance will emerge.

So it will be with WFH.

A Key Word of Warning

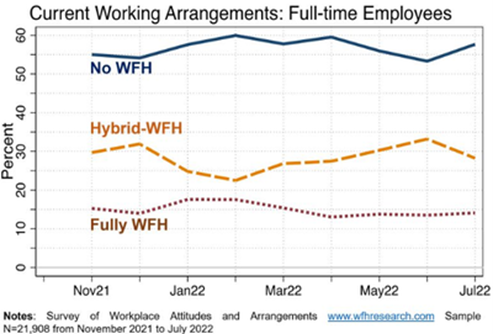

In a recent post on LinkedIn, Professor Nick Bloom of Stanford University suggests that work from home (WFH) has stabilized into three groups:

- No WFH: 55% of employees, mostly in face-to-face jobs in retail, manufacturing, foodservice etc.;

- Hybrid-WFH: 30% of employees, typically better paid managers and professionals; and

- Fully-WFH: 15% of employees in support roles like IT and payroll.

According to Bloom, the shift to WFH is the largest shock to labour markets in decades. Pre-pandemic WFH was trending towards 5% of days by 2022. Now WFH has stabilized at 30%, a 6-fold jump. In America alone this is saving about 200 million hours and 6 billion miles of commuting a week.

The word of warning is this: WFH will only ever be available to a minority, even if a sizable minority. Most workers will still have to turn up and put in a shift in a place of work. This applies not just to those who must work machines in factories, or wait tables in restaurants, or cut hair or do manicures.

It also applies to many highly skilled professionals such as doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, on-site engineers, airline pilots, train drivers and many others.

We need to be careful, as we have written before, about the emergence of a new “industrial divide”, a divide between those who can work from anywhere, anytime, and those who need to present in person every working day. The social contribution of many of those who have to turn up daily is way more valuable than that of some hipster sitting on a beach writing a few lines of code for a computer game.

If WFH is sold as improving work/life balance, and it does, then managements concerned about the future wellbeing of their organisations will also need to ask how they can improve the work/life balance of those who must be there, in-person, every day. The better life cannot just be the preserve of those living off their laptops.

Gen X and Gen Z is Not the World

A friend drew my attention to this article about Gen X and Gen Z. Now, to be absolutely honest, I have no idea whether Gen X and Gen Z actually exist outside the world of marketing categories and academics trying to sell their latest book on an imagined cultural phenomenon. But as they say, the hustle is the hustle, and I am not going to knock it other than to call it for what it is.

But if X and Z do exist, they exist in a very small corner of the world, possible somewhere in California and other US coastal cities. Maybe the odd European city too. Which includes London as Brexiteers have not yet figured out how to move it to Asia.

Too often we make the mistake of seeing these small corners for the whole building. Take this from the article:

“Millennial hustle culture is very similar to the Baby Boomer workaholic culture — and that is what Gen Z is pushing back on, similar to the reaction Gen X-ers had to the Boomers doing that,” says Dr. Megan Gerhardt, author of Gentelligence: The Revolutionary Approach to Leading an Intergenerational Workforce. Both generations have instead chosen to opt-out of a certain get-ahead-at-all-costs culture in favor of searching for more meaningful work.

What is “meaningful work’? All work is meaningful in some sense to someone, or else it would not exist. Collection garbage is very meaningful work for most communities. If in doubt about this read what happens when garbage collectors stop work: Scottish bin strike

What I suspect the author means by “meaningful work” is work that makes Z-ers feel good about themselves, work that plays to their moral sensibilities. Lucky them.

Most people on the planet just want to have a job that allows them to look after themselves and their families. Have a look at something like this to get a sense of non-Z realities.

As I write this, millions of otherwise decently paid workers in the UK are wondering how they will be able to cover their winter fuel bills, with the average household predicted to have to find around £3,549 per annum from October, and this may jump to more than £6,000 from sometime next year.

But then if you are an academic trying to “hustle” a book about how to manage angst-ridden Z-ers desperately seeking existential meaning, West Coast tech company executives are probably a better market, than talking about fuel poverty in the UK or precarious work in some dodgy building in Bangladesh.

Or this:

Retiring CEO of Whole Foods John Mackey made news in all the wrong ways when he said that meaningful work was something that had to be earned not given. Not so for Gen Z, who expect to be doing work they care about out of the gate.

If you care about something, go and do something about it. Workplaces are not social movements. They are what they say on the label: workplaces. Places where goods are made or sold, or services are created or delivered.

It is the job of Otis to make and service the best elevators it can. It does good by helping people move easily within buildings. The good results from its elevators. Similarly, Apple does good by helping people connect. But neither Otis nor Apple are in business to “do good”. They are commercial corporations, interested in stockholder returns. So, if you work for a commercial corporation, how do you define work you “care about out the gate’?

Google began life with the mission statement that included the phrase: “Don’t be evil.” But define “evil”? More importantly, who gets to define what is evil? Lockheed makes military jets. Is that evil? Are clinics which provide abortion services good or evil? Are organisations which provide assistance to non-documented immigrants good or evil? Is fast food good or evil? Should a US company stay in Russia to help feed the population? What about the use of fossil fuels?

In a world of political and moral partisanship there are no template answers to such questions. Just ask Disney about Florida.

Are we heading for a world where corporations must pick sides and Z-ers will only go to work for companies on their side?

Try to dance down the middle of the road and one side or the other will come for you.

“Quiet Quitting”: Nothing New Under the Sun

“The eye never has enough of seeing, nor the ear its fill of hearing. What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun. Is there anything of which one can say, "Look! This is something new"? (Ecclesiastes 1: 9)”

“Quiet quitting” is nothing new. Anyone familiar with office life over the years knows it is an age-old phenomenon. While offices have always been full of go-getters and strivers, people ready to work all the hours on the clock and more if they could, they have also been full of those who clocked out promptly, whether to go home to the family, to the golf course, or wherever else their hearts lay.

The quitters just did not talk about it. Or at least they didn’t before social media. Whereas once a couple of “quitters” might have chatted to one another over a drink in the bar around the corner, “thank God we are out of there”, now some feel that they need to engage with the wider world on their work philosophy of “just do what it takes”.

The great and the good of the world of work have gone into a funk over people stating the obvious that they just do “all I need to get by, to borrow from Marvin Gaye.” You would think that the very moral foundations of capitalism are being undermined because some people are now saying publicly that they are not prepared to work till they drop. That they want out of the 24/7 “hustle culture’.

Ever since Drucker first identified “knowledge workers” as essential to modern corporations, managers have been obsessed with “motivation”. How do you get the best out of such workers? Or, as a Marxist might put it, how do you extract maximum surplus value?

The work/wage contract is inexact. The worker offers their skills (note: not their “whole self”) for a certain number of hours a day in return for wages and benefits. That much is exact. But no contract can state how much effort a knowledge worker must put in during those hours.

It has always been different for manufacturing workers, subject to machine and Taylorist disciplines. No manager ever much worried about the motivation of someone sitting on a production line for eight hours a day, doing the same task over and over. Marcuse captures the anomie of such work in One Dimensional Man.

Hence the whole motivation and engagement industry. How do we structure organisations, design incentives, develop managers to get the best out of the brains of knowledge workers? There is no right answer which is why every so often a new fad comes along and the consultants promoting the fad get rich and are gone by the time managers find it does not work.

It is a labour of Sisyphus, forever condemned to push the boulder to the top of the mountain, over to see it roll down to the bottom again just as the peak is in sight.

“Quiet quitting” has always been with us and always will. It is just that it has now gone public.

Europe is different

While the organisation of work may be a unilateral management decision in the US, Europe is a different matter. With a dense network of both European Union and national laws governing working time, health and safety, data rights, and information and consultation obligations, working arrangements must be negotiated. Much neglected during the emergence rush to remote during Covid, these rules will increasingly come into focus as remote/hybrid work gets built into organisational structures for the future.

European workplaces must conform to standards. If a major company has, say, 100,000 workers based in a couple of dozen locations across France, it can have teams in place to ensure that these workplaces are fit for purpose. Everything from the physical layout of the buildings to the safety and security of IT systems, can be monitored and managed properly.

If 60% of the workforce now opt to work remotely for two or three days a week, that creates 60,000 new workplaces. If these workplaces are also homes, how do you ensure that these homes are fit for office work purposes? Does tripping over the dog as you go to make a coffee constitute a work accident? How do you ensure the security of computers connected to home internets?

Who pays for what? While workers may save on commuting costs, the company is saving on office costs. As we head into a winter or rapidly rising energy bills, who pays for home heating and other utilities? Should the company be “renting” office space from the employees?

What about the ethics of employee monitoring in the privacy of their own home? Remote work has seen the rapid development of surveillance tools, sophisticated software that can track everything from keyboard strokes to facial expressions, and websites visited.

These tools remind me of those hangers you find in some hotels that cannot be taken from the rail and that scream “we don’t trust you not to steal them.” These software tolls give employees the same message: if we are not watching you, you will skive and not work.

If these tools are AI-based, with algorithms making human resource decisions, then they will increasingly need to be subject to employee information, not only under the GDPR, but also the emerging legislation of AI governance, and in specific legislation on platform workers and gender pay transparency.

The European social partners, BusinessEurope and the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) have agreed to open negotiations on a new framework covering these issues. If they manage to reach an agreement it will be turned into law under the EU Treaty provisions on social dialogue. These discussions will be difficult but if agreement can be found, it will be beneficial for all concerned.

Finally

Covid has changed everything. There is no going back. The past is another country. Now, we are exploring new frontiers. Opportunities and dangers lie ahead.

Tom Hayes

Director of European Union and Global Labor Affairs, HR Policy Association

Contact Tom Hayes LinkedIn